How We Built a Billing System That Scaled with Us from $40M ARR to ~$140M

Create AI videos with 240+ avatars in 160+ languages.

Startups always have to make tough decisions about where to invest. You don’t become a mature enterprise overnight, and that means you will, inevitably, have to work with non-ideal systems for long periods of time.

In our case, one of these tough decisions was billing management. Synthesia scaled to $40M ARR without a proper billing system. We had billing limits in theory, but we didn’t enforce them in practice. We relied on what was effectively an honor system to prevent users from exceeding their allotted video usage.

Of course, this couldn’t last. Eventually, we hit pain points: our user base had grown, and it became increasingly difficult to identify which customers had access to which features. Sales-led clients were especially hard.

We came to a decision and then a fork in the road: We clearly needed a billing system to continue scaling, but no vendor offered a feature set that met our needs. This wasn’t a one-and-done issue, however, so we needed to build a solution, and we needed it to grow with us.

The core requirement for this system was the ability to enforce usage and feature limits, but it also had to be:

- Flexible

- Easy to maintain

- Easy to extend and scale

When I started working at Synthesia in 2023, this was my primary project, and for most of its development, I was its only engineer. It took us about three months to build, and about a month later, we completed migrating over $40 million in usage onto the new system.

This billing system was simultaneously bespoke to our specific needs and built to scale. Over the past three years, Synthesia has scaled from $40 million in ARR to $140 million in ARR, and this system has enabled us to grow, adapt, and iterate throughout.

We’re now retiring it, and we wanted to look back at how this system has helped us reach this point.

Flexibility through isolation

Flexibility and isolation were our primary technical principles: we wanted every element to be isolated from every other element – including internal and external elements – so that we could iterate on the system over time, component by component.

Internal isolation

We emphasized internal isolation in the first RFC, well before we actually started building it.

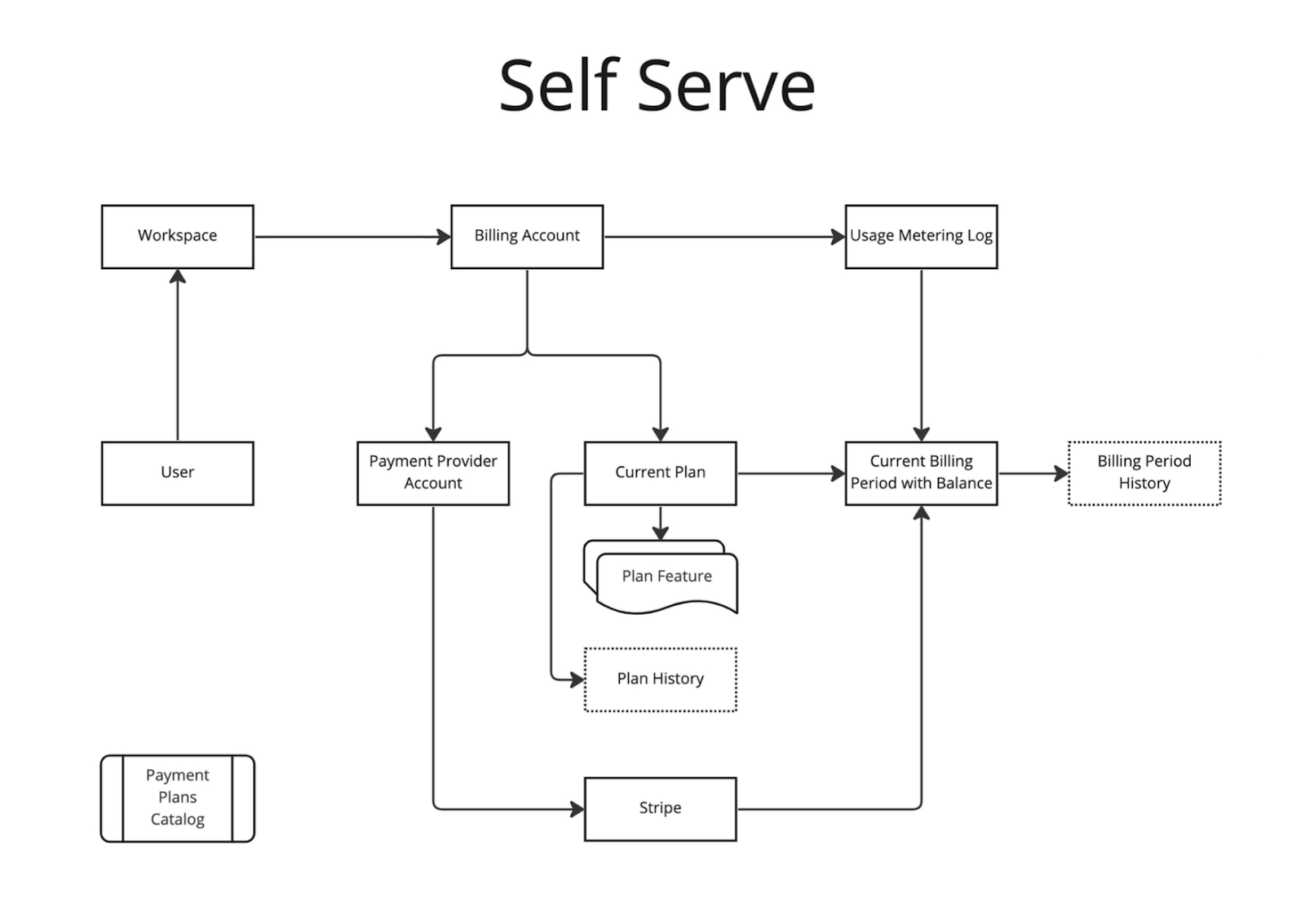

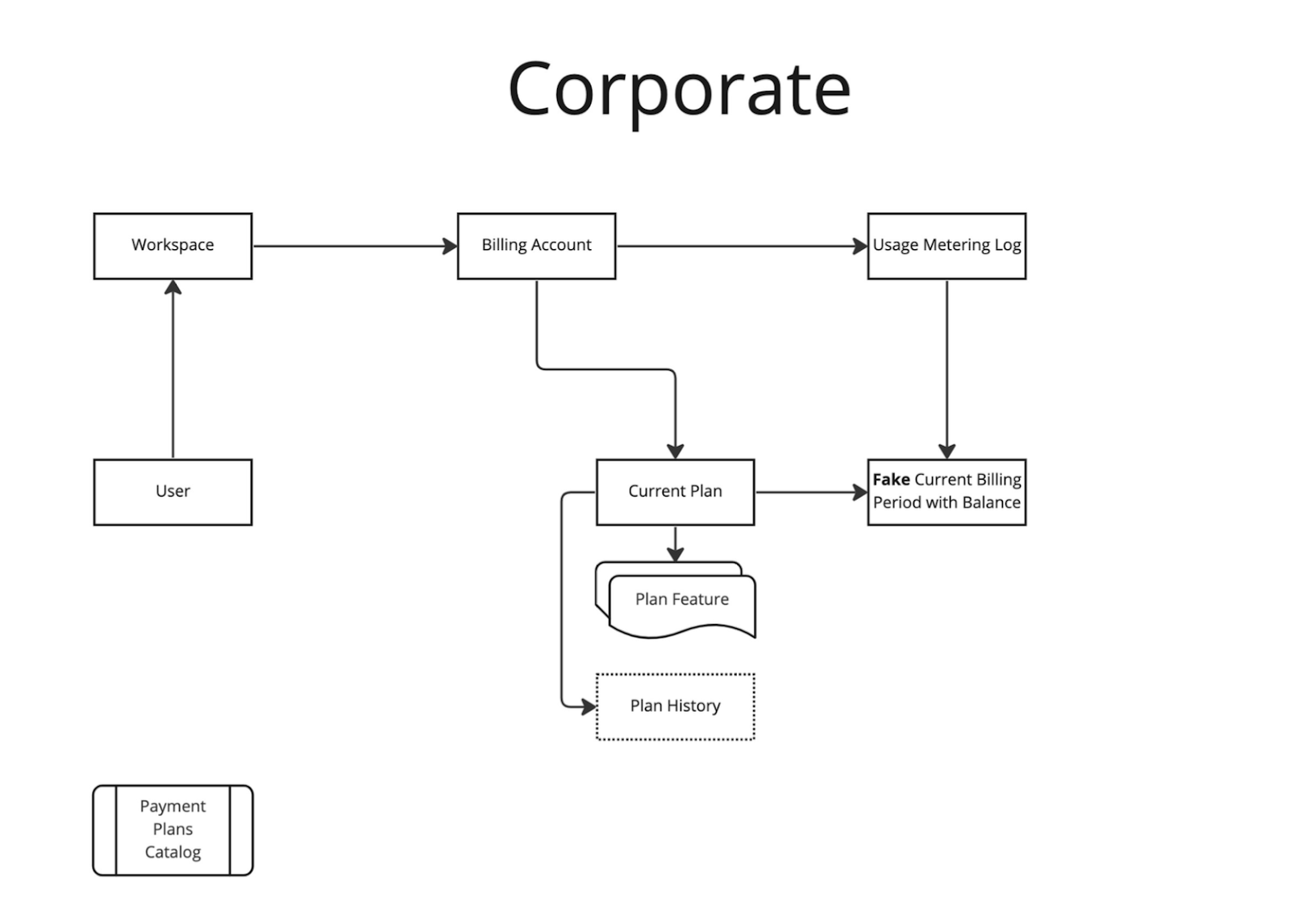

First, the billing system needed to be isolated from the business entities in the product. Instead of tying the system to the business entities, we connected them via an intermediary: the billing accounts. Each billing account is assigned to a paying customer, and it’s through these that the billing system communicates with any given business entity.

In the diagrams below, taken from our original RFC, you can see this pattern in each, both in the self-serve flow and the Enterprise flow.

This meant we didn’t have to modify the billing implementation to support different types of customers, especially if and when our customers changed over time. Remember, we were building for the medium-term, if not the long-term, so it needed to be flexible enough to support design choices we couldn’t necessarily anticipate.

For example, the types of customers we supported changed over time, and the billing system supported each transition. Initially, our customers were individuals, and later we added workspaces to allow multiple individuals to collaborate. After that, we allowed organizations to have multiple workspaces. The design of the billing system allowed us to gradually transition between these customer types without having to rebuild it.

This was all easy to do because the billing system was internally isolated. All we had to do was link new billing accounts.

External isolation (Stripe and Salesforce)

Stripe is our payment provider, and our goal was to maintain an independent data model from Stripe. We wanted to isolate the billing system from the payment provider to, again, maintain flexibility.

To do this, we abstracted any data modeling that came from Stripe and wasn’t closely integrated into our model. Any tight integration with Stripe would have risked preventing us from using other payment providers down the line – if, for some reason, we needed to.

With the new billing system, all we’d have to do is add a new link to a new payment provider to map it into our payment plan. If necessary, we could even run different payment providers in parallel. For Enterprise plans, the same model applied, except without Stripe.

Salesforce was our CRM, and our goal was similar – isolate for the sake of flexibility.

Salesforce follows the same pattern. Because the system maintained isolation, we just needed a new link if we wanted to use a different CRM. That meant we could easily transfer a Salesforce contract to a billing account or payment plan, too. Thanks to isolation, if we ever decided to use a different CRM, we could just swap it in.

Building a payment-billing-usage loop

The core structure of our billing system was a loop that connected feature purchases to billing periods and usage tracking. The payment plan defines what users have access to; the billing period reflects the current balance; and we track usage in real-time to gate feature access. No more honor system.

Payment

The payment plan is essentially a list of features that a given customer has purchased and has access to.

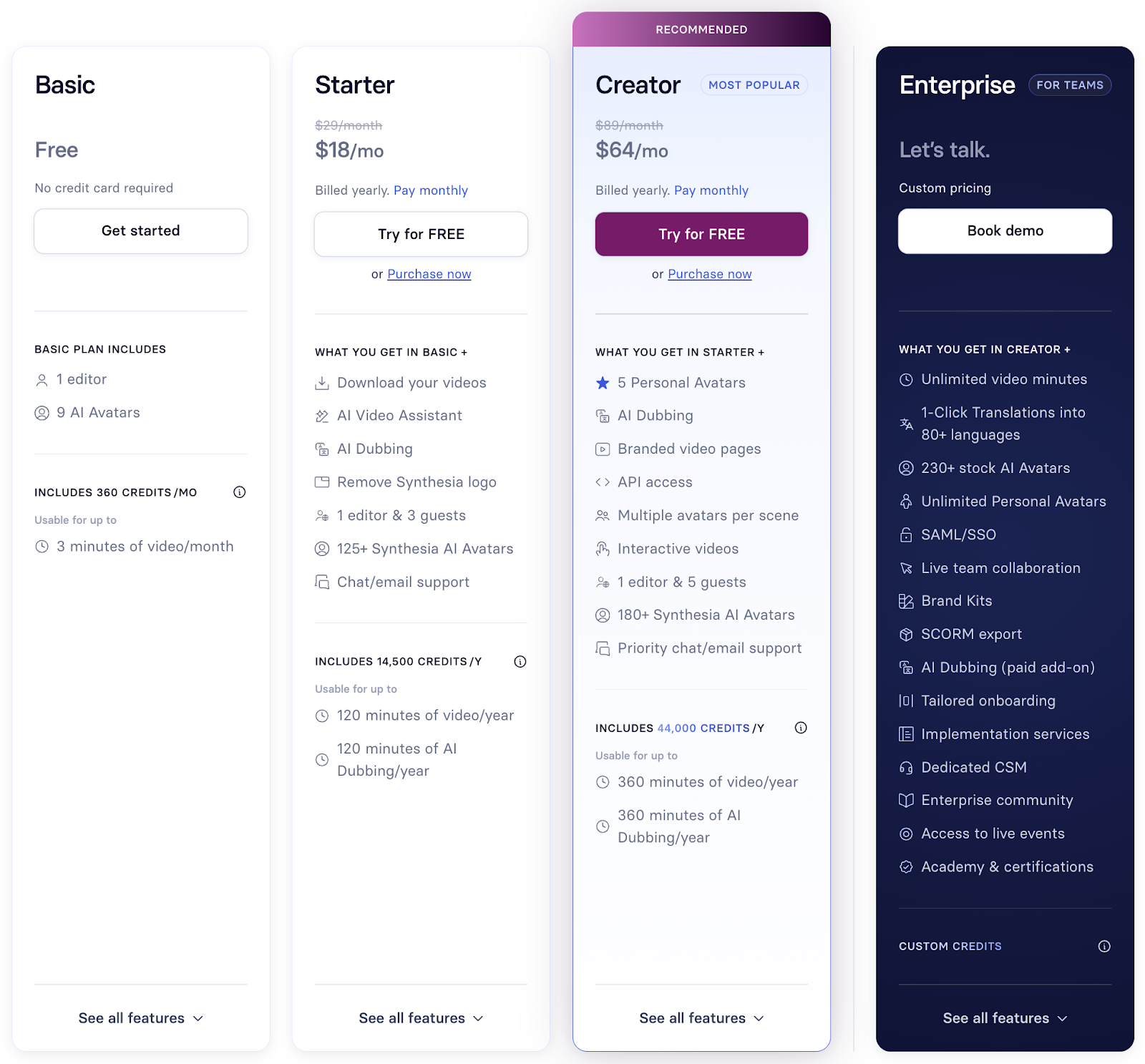

For Synthesia today, plans include Basic, which is free and has limited features, Starter and Creator, which cost $18/month and $64/month, respectively, and have many more features, and Enterprise, which has custom pricing and complete feature access.

Users in a given plan need to be granted those features and gated from features they haven’t paid for. If a Basic user upgrades, for example, the billing system needs to offer them the ability to download videos (from the Starter plan) and gate them from API access (from the Creator plan).

Attributes across these plans include:

- Self-serve vs. Enterprise

- Start date

- Billing interval

So, the billing system also needs to track the type of customer each user is, when they started paying, the Stripe configuration, and the billing interval (i.e., when they’re charged every month).

Billing

The billing period aligns with the payment plan structure, and we use it to track the amount of video generation and other products/features our customers have used. This enables real-time balance updates, rather than aggregating queries, which is helpful for us as we monitor usage and for users as they track what they can still do over a given period.

For example, if the payment plan says that a user has ten minutes of video generation per month and the user generates five minutes, the billing period would show a balance of five minutes remaining.

Usage metering

Usage metering is how we maintain a comprehensive history of usage that tracks all activity and supports audit logging. This is an immutable log of events that shows, for example, that five minutes of video generation have been used at a given point in time for a specific video. This ensures that users are not double-charged for the same video.

We considered alternate ways to build this, but decided against them. If you don’t have the notion of a current balance and want to understand whether a user can generate a new video, you’d need to query the usage metering log. That would require aggregating all the events to understand the current balance, which can make the query too slow.

In contrast, since we have a separate place that’s updated every time a new usage event occurs, we can offer real-time updates.

MongoDB: An unorthodox building block

In the real world, you don’t get to pick your tools from a blank slate. MongoDB was already running at Synthesia, supporting our database system, and that made it the most practical choice for the billing system, even if it wouldn’t have been the obvious choice otherwise. We adapted it, using what we learned from relational databases, to support billing.

How we made MongoDB work

MongoDB is an unorthodox choice for this type of project. Typically, for billing systems, you’d choose a database that has a very high guarantee of data integrity (usually a relational database instead of a NoSQL database).

As a result, figuring out how to use MongoDB for these purposes was one of our first big challenges.

One way to do this, which we rejected, was to create a master document that defined each feature and linked it to a payment plan for each customer. When we provisioned a customer, we’d link to the master document, and that would define the features they had access to.

We instead adopted an approach where there are no references to shared objects for each customer. Instead, every customer gets their own copy of the payment plan, billing account, and billing period. That ensured we could modify plans for all customers through the master document and gate features for specific customers without affecting the rest of them.

Benefits and tradeoffs

The primary advantage of this approach is that it gives us the flexibility to override and adjust the payment plan for each individual customer, independent of others.

This approach also meant we could control how we released features. In the typical approach, changing the master document affects every instance that references it. With our approach, we could determine how we wanted to migrate existing users to the new features. The downside is data migration, which is not well supported in MongoDB.

Testing and verification are also easy, because you can create a test account, easily assign it a custom plan, make changes to its instance, and then roll it out to everyone.

Adapting patterns

One of my first priorities for this project, and one of the first we outlined in our initial RFC, was finding patterns we could adapt to our use case. We ultimately used the Document Versioning, Extended Reference, and Bucket patterns, which are specific to MongoDB, and were central to our approach.

In the Document Versioning pattern, we retain older data versions in a separate collection from the current data. This pattern, as described in the documentation, allowed us to maintain current documents and their history in the same database, eliminating the need for multiple systems to manage old data history.

In the Extended Reference pattern, we maintain separate collections of customer data, but, rather than duplicating the information from each customer, we only copy frequently accessed fields. For example, in our structure, you’d have had to get the billing account, then the plan account, and then the payment plan, all to determine whether a user has access to a given feature. This can be inefficient.

With a standard reference, we can copy some of the most used fields in the document that reference them and send references to them, so we don’t have to do lookups all the time. And in our billing accounts, we have payment plan summaries that include duplicated details, such as name, type, status, and date.

Another important pattern for us was the Bucket Pattern, which we used for usage metering. This pattern allows you to bucket data together, which makes it easier to sort and organize groups of data.

For our purposes, the bucket is a small record of events that we can shove into a MongoDB collection and query. We can build analytics on top of the bucket because it includes all event history. We can then attach all sorts of metadata and export it to a data processing platform for analytics.

Our user reporting, for example, is based on this table (e.g., “this month, you used 10 minutes”), and it shows which video consumed how many minutes.

How we migrated $40M usage in 3 months

The migration was going to be complex for the same reasons we needed to build a new billing system in the first place: We wanted to ensure that we correctly represented the features that customers had paid for, and we needed to move them all to a system where that was easier to manage without losing track of what they had paid for already.

It was similarly tricky to track some of our sales-led customers. Some of them were in Salesforce, which enabled us to correlate those contacts by email address. But many sales-led customers were users who didn’t pay at all. These included demo accounts, job applicants who got access as part of the interview process, and influencers who got access as part of a marketing campaign.

Once we had finally captured every account and edge case we could, we introduced a legacy plan for any remaining customers that we couldn’t assign to a specific plan. We didn’t want to block access, so we put them on a legacy plan and set an expiration date to give them a chance to choose new plans.

The most difficult part of the migration wasn’t even the billing functionalities. The complexity of this migration became even more difficult because a new feature – workspaces – was launching at the same time.

For a while, we had two systems in motion, but we managed to juggle both without incident. We first migrated all the usage queries to workspaces and then redirected those to the new billing system. Ultimately, the flexibility of the billing system itself was a key part of migrating to it.

Advantages and tradeoffs

The billing system functioned how we needed it to on day one, but it was the flexibility it enabled in the years after – as well as the tradeoffs it minimized – that allowed us to grow.

Flexibility over time

In 2025, we transitioned all payment plans to a credit-based system, and thanks to this new billing system, we successfully completed the move in just one month.

Previously, users would purchase a specific amount of video time, and the billing system tracked their usage accordingly. After, every plan provided a set number of credits per month, and users could spend them on any of the features their plan allowed. Usage corresponded with an exchange rate, too – one minute of video might be worth 100 credits, for example.

Without a billing system or with one that was less well-designed, this change would have taken significantly longer, and we might have fallen behind other AI companies, where credit-based systems were becoming the norm.

Minimizing tradeoffs

Of course, there were trade-offs, but thanks to our design principles, we stayed focused on what mattered most, and the trade-offs were relatively minimal.

The biggest gap, perhaps, is that we didn’t build much lifecycle management for sales-led plans. We didn’t do this because we didn’t have an integration with business systems, like Salesforce, that salespeople could have used to manage those plans.

As a result, lifecycle management was still manual. When salespeople got a new contract, they had to fill in the details manually. Then, we’d transfer the contract with the customer into the product.

The billing system also never supported annual contracts with monthly invoices. We could have supported this if we had wanted to, but there wasn’t enough demand, and we chose not to build it.

We also didn’t build features we determined we didn't need at the time. For example, there is no mention of price recurrences in the system, invoices, or receipts. External systems track all these things.

A bridge to what’s next

For quite a while, the billing system we built didn’t need changes after we migrated everyone. Adding credits was the only significant change, and that barely took a month.

We are now retiring the billing system and moving to an external provider.

For the past three years, this system has been low-maintenance, enabling us to grow, iterate, and change. It was a low-overhead, powerful, fundamental lever for the business, all supported, almost entirely, by one engineer.

We’re only now running into opportunities for growth that this billing system can’t easily serve. For example, our finance teams now want data to support reporting. We could build this into the billing system, but serving this need and others would take time. By moving to an external provider – one that offers features and functionality none did three years ago – we can capitalize on these growth opportunities more quickly.

This is the natural lifecycle of a homegrown system, but it’s the ideal version of this lifecycle. Now, we can move on, but we've come quite far with it and couldn’t have gotten here without it.

About the author

Software Engineer

Boian Tzonev

Boian Tzonev is a software engineer at Synthesia, working on billing, payments, and growth systems. Previously, he built large-scale billing and ledger platforms at Uber, with a focus on distributed systems and domain-driven design.